“He [Vivekananda] was energy personified, and action was his message to men. For him, as for Beethoven, it was the root of all the virtues. …

His pre-eminent characteristic was kingliness. He was a born king and nobody ever came near him either in India or America without paying homage to his majesty.

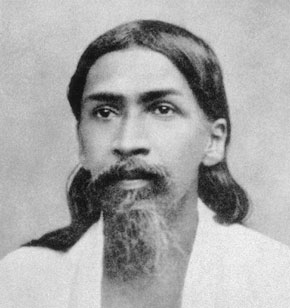

When this quite unknown young man of thirty appeared in Chicago at the inaugural meeting of the Parliament of Religions, opened in September 1893, by Cardinal Gibbons, all his fellow members were forgotten in his commanding presence. His strength and beauty, the grace and dignity of his bearing, the dark light of his eyes, his imposing appearance, and from the moment he began to speak, the splendid music of his rich deep voice enthralled the vast audience of American Anglo-Saxons, previously prejudiced against him on account of his colour. The thought of this warrior prophet of India left a deep mark upon the United States.

It was impossible to imagine him in the second place. Wherever he went he was the first. …Everybody recognized in him at sight the leader, the anointed of God, the man marked with the stamp of the power to command. A traveller who crossed his path in the Himalayas without knowing who he was, stopped in amazement, and cried, ‘øiva !…’

It was as if his chosen God had imprinted His name upon his forehead. …

He was less than forty years of age when the athlete lay stretched upon the pyre. …

But the flame of that pyre is still alight today. From his ashes, like those of the Phoenix of old, has sprung anew the conscience of India—the magic bird—faith in her unity and in the Great Message, brooded over from Vedic times by the dreaming spirit of his ancient race—the message for which it must render account to the rest of mankind.

Moving as were his [Vivekananda’s] lectures at Colombo, and the preaching to the people of Rameswaram—it was for Madras that he reserved his greatest efforts. Madras had been expecting him for weeks in a kind of passionate delirium….

He replied to the frenzied expectancy of the people by his Message to India, a conch sounding the resurrection of the land of Ràma, of øiva, of Kçùõa, and calling the heroic Spirit, the immortal àtman, to march to war. He was a general, explaining his Plan of Campaign, and calling his people to rise en masse : ‘My India, arise !’…

‘For the next fifty years… let all other vain Gods disappear for that time from our minds. This is the only God that is awake, our own race—everywhere His hands, everywhere His feet, everywhere His ears, He covers everything. All other Gods are sleeping. What vain Gods shall we go after and yet cannot worship the God that we see all round us, the Viràñ ?… The first of all worship is the worship of the Viràñ—of those all around us. … These are all our Gods—men and animals, and the first Gods we have to worship are our own countrymen. …’

Imagine the thunderous reverberations of these words!… The storm passed ; it scattered its cataracts of water and fire over the plain, and its formidable appeal to the Force of the Soul, to the God sleeping in man and His illimitable possibilities ! I can see the Mage erect, his arm raised, like Jesus above the tomb of Lazarus in Rembrandt’s engraving : with energy flowing from his gesture of command to raise the dead and bring him to life. …

Did the dead arise ? Did India, thrilling to the sound of his words, reply to the hope of her herald? Was her noisy enthusiasm translated into deeds ? At the time nearly all this flame seemed to have been lost in smoke. Two years afterwards Vivekananda declared bitterly that the harvests of young men necessary for his army had not come from India. It is impossible to change in a moment the habits of a people buried in a Dream, enslaved by prejudice, and allowing themselves to fail under the weight of the slightest effort. But the Master’s rough scourge made her turn for the first time in her sleep, and for the first time the heroic trumpet sounded in the midst of her dream the Forward March of India, conscious of her God. She never forgot it. From that day the awakening of the torpid Colossus began. If the generation that followed, saw, three years after Vivekananda’s death, the revolt of Bengal, the prelude to the great movement of Tilak and Gandhi, if India today has definitely taken part in the collective action of organized masses, it is due to the initial shock, to the mighty ‘Lazarus, come forth;’ of the message from Madras. This message of energy had a double meaning : a national and a universal. Although, for the great monk of the Advaita, it was the universal meaning that predominated, it was the other that revived the sinews of India.

His words are great music, phrases in the style of Beethoven, stirring rhythms like the march of Handel choruses. I cannot touch these sayings of his, scattered as they are through the pages of books at thirty years’ distance, without receiving a thrill through my body like an electric shock. And what shocks, what transports must have been produced when in burning words they issued from the lips of the hero !

India was hauled out of the shifting sands of barren speculation wherein she had been engulfed for centuries, by the hand of one of her own sannyàsins; and the result was that the whole reservoir of mysticism, sleeping beneath, broke its bounds and spread by a series of great ripples into action. The West ought to be aware of the tremendous energies liberated by these means.

The world finds itself face to face with an awakening India. Its huge prostrate body, lying along the whole length of the immense peninsula, is stretching its limbs and collecting its scattered forces. Whatever the part played in this reawakening by the three generations of trumpeters during the previous century—(the greatest of whom we salute, the genial Precursor : Rammohun Roy), the decisive call was the trumpet blast of the lectures delivered at Colombo and Madras.

And the magic watchword was Unity. Unity of every Indian man and woman (and world-unity as well) ; of all the powers of the spirit—dream and action ; reason, love, and work. Unity of the hundred races of India with their hundred different tongues and hundred thousand gods springing from the same religious centre, the core of present and future reconstruction. Unity of the thousand sects of Hinduism. Unity within the vast Ocean of all religious thought and all rivers past and present, Western and Eastern. For—and herein lies the difference between the awakening of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda and that of Rammohun Roy and the Bràhmo Samàj—in these days lndia refuses allegiance to the imperious civilization of the West, she defends her own ideas, she has stepped into her age-long heritage with the firm intention not to sacrifice any part of it, but to allow the rest of the world to profit by it, and to receive in return the intellectual conquests of the West. The time is past for the pre-eminence of one incomplete and partial civilization. Asia and Europe, the two giants, are standing face to face as equals for the first time. If they are wise they will work together, and the fruit of their labours will be for all.

This ‘greater India’, this new India—whose growth politicians and learned men have, ostrich fashion, hidden from us and whose striking effects are now apparent—is impregnated with the soul of Ramakrishna. The twin star of the Paramahansa and the hero who translated his thoughts into action, dominates and guides her present destinies. Its warm radiance is the leaven working within the soil of India and fertilizing it. The present leaders of India : the king of thinkers, the king of poets, and the Mahàtmà—Aurobindo Ghosh, Tagore, and Gandhi—have grown, flowered, and borne fruit under the double constellation of the Swan and the Eagle—a fact publicly acknowledged by Aurobindo and Gandhi. …

As for Tagore, whose Goethe-like genius stands at the junction of all the rivers of India, it is permissible to presume that in him are united and harmonized the two currents of the Bràhmo Samàj (transmitted to him by his father, the Maharshi) and of the new Vedantism of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda. Rich in both, free in both, he has serenely wedded the West and the East in his own spirit. From the social and national point of view his only public announcement of his ideas was, if I am not mistaken, about 1906 at the beginning of the Swade÷ã movement, four years after Vivekananda’s death. There is no doubt that the breath of such a Forerunner must have played some part in his evolution.

I was glad to hear Gandhi’s voice quite recently—in spite of the fact that his temperament is the antithesis of Ramakrishna’s or Vivekananda’s—remind his brethren of the International Fellowships, whose pious zeal disposed them to evangelize, of the great universal principle of religious ‘Acceptation’, the same preached by Vivekananda.

At this stage of human evolution, wherein both blind and conscious forces are driving all natures to draw together for ‘co- operation or death’, it is absolutely essential that the human consciousness should be impregnated with it, until this indispensable principle becomes an axiom : that every faith has an equal right to live, and that there is an equal duty incumbent upon every man to respect that which his neighbour respects. In my opinion Gandhi, when he stated it so frankly, showed himself to be the heir of Ramakrishna.

There is no single one of us who cannot take this lesson to heart. The writer of these lines—he has vaguely aspired to this wide comprehension all through his life—feels only too deeply at this moment how many are his shortcomings in spite of his aspirations; and he is grateful for Gandhi’s great lesson—the same lesson that was preached by Vivekananda, and still more by Ramakrishna —to help him to achieve it.”

Romain Rolland (1866-1944)

Romain Rolland was a French man of letters. Received 1915 Nobel Prize for literature. His works included Jean Christophe (1904-1912) and pacifist manifestos collected in An-dessus d‚ lamelee (1915), second novel cycle L’àme- enchante‚ (1922-1933); historical and philosophical plays collected in Le Theatre de la revolution and Les Tragedies de la foi (1913); biographies Beethoven (1903), Michel-Angelo (1905), Tolstoi (1911), and Mahatma Gandhi (1924), The Life of Ramakrishna, The Life of Vivekananda and the Universal Gospel.

Leave A Comment