Divine Foundation

At the time of Sri Ramakrishna’s advent India’s ancient system of education and training was disappearing. The youth brought up in an occupied land began to identify with their occupiers and to doubt the religion and traditions that, to them, had led to such subjugation. They began imitating the West and saw India’s religious traditions as obstacles to their entering the modern world. But all attempts to revitalize India by destroying the traditions that had sustained her were bound to fail. Swami Saradananda asks: ‘How can India, whose soul is religion, survive if her religion is not restored to life? How is it possible for the atheistic West to eradicate the religious degradation that resulted from its own materialism?’

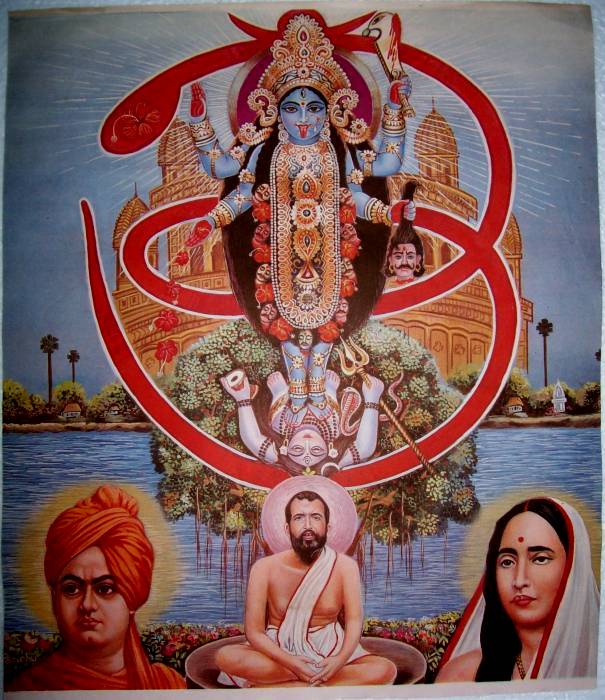

Vivekananda and Kali

Mother Kali was Sri Ramakrishna’s overwhelming reality. He sang to her, had visions of her, spoke intimately to her, and heard her voice. It was only by accepting Mother Kali that Swamiji could fully accept Sri Ramakrishna and become his pure instrument. The Master had already seen Narendra’s future in a vision. He understood that it was Narendra who would lead his disciples and devotees to accomplish the Mother’s mission in the world. But the young Narendra, like much of young Bengal, had been swayed by the persuasive teachings of Keshabchandra Sen and the Brahmo Samaj. The Samaj and the other socio-religious groups of the day, responded to the challenge of the West, not with atheism, but with a ‘Christianized’ form of Hinduism. In their attempt to purify Hinduism of what they saw as superstition, they preached that the various deities were false, and its members even signed loyalty oaths vowing not to bow down before images. Thus, Narenda’s close association with Sri Ramakrishna created a great dilemma for him, for he had witnessed the Master’s power, purity, and devotion, but could not accept the Hindu world that the Master lived in: a world of gods and goddesses, of ‘graven’ images, of visions and ecstasies. Swamiji later said of this time: ‘How I used to hate Kali! … and all Her ways! That was the ground of my six years’ fight—that I would not accept Her. … I loved him [Sri Ramakrishna], you see, and that was what held me. I saw his marvellous purity. … I felt his wonderful love. … His greatness had not dawned on me then. All that came after wards when I had given in. At that time I thought him a brain-sick baby, always seeing visions and the rest. I hated it. And then I too had to accept Her! ’

It occurred to me that God grants the Master’s prayers, so I should ask him to pray on my behalf that my family’s financial crises would be overcome. I was sure that he wouldn’t refuse, for my sake. I rushed to Dakshineswar and importuned him, saying, ‘Sir, you must speak to the Divine Mother so that my family’s financial problems can be solved.’ The Master replied: ‘I can’t make such demands. Why don’t you go and ask the Mother yourself. You don’t accept the Mother—that is why you have all these troubles.’ I replied: ‘I don’t know the Mother. Please tell the Mother for me. You have to, or I won’t let you go.’ The Master said affectionately: ‘My boy, I’ve prayed many times to the Mother to remove your suffering. But She doesn’t listen to my prayers because you don’t care for Her. All right, today is Tuesday, a day especially sacred to Mother. Go to the temple tonight and pray. Mother will grant whatever you ask for, I promise you that. My Mother is the embodiment of Pure Consciousness, the Power of Brahman, and She has produced this universe by mere will. What can She not do, if She wishes?’

When the Master said that, I was fully convinced that all my suffering would cease as soon as I prayed to Her. I waited impatiently for night. At 9.00 p.m. the Master told me to go to the temple. On my way, I was possessedby a kind of drunkenness and began to stagger. I firmly believed that I would see the Mother and hear Her voice. I forgot everything else and became absorbed in that thought alone. When I entered the temple, I saw that the Mother was actually conscious and living, the fountainhead of infinite love and beauty. Overwhelmed with love and devotion, I bowed down to Her again and again, praying, ‘Mother—grant me discrimination, grant me detachment, grant me divine knowledge and devotion, grant that I may see You without obstruction, always!’ My heart was filled with peace. The universe disappeared from my mind and the Mother alone occupied it completely.

Mother, Thou art our sole Redeemer,Thou the support of the three gunas,Higher than the most high.Thou art compassionate, I know,Who takest away our bitter grief.Thou art in earth, in water Thou;Thou liest as the root of all.In me, in every creature,Thou hast Thy home;though clothed with form,Yet art Thou formless Reality.Sandhya art Thou, and Gayatri;Thou dost sustain this universe.Mother, the Help art ThouOf those who have no help but Thee,O Eternal Beloved of Shiva!.

‘Mother’s Work’

Another example of Swamiji’s legacy is Kali Mandir in Laguna Beach, California. In 1993 Elizabeth Usha Harding, author of Kali, the Black Goddess of Dakshineswar, arranged for a beautiful Kali image to be brought from India, which was ritually awakened by Ha radhan Chakraborti, the late main priest of the Dakshineswar Kali temple. He named her Sri Ma Dakshineswari Kali and explained that because the image was now ‘alive’, she needed to be worshipped every day. And Mother arranged for her worship, as devotees who had very little background in the intricacies of India’s temple puja standards now found themselves gradually adopting this vastly rich devotional tradition one detail at a time—out of a simple love and desire to please Mother. Haradhanji and his assistant Pranab Ghosal came annually for seventeen years, teaching the devotees Kali puja as practised in Dakshineswar since the time of Sri Ramakrishna.

There was never an intention to start a temple or establish a monastery. Over time this simple daily worship grew organically and slowly took on the form of a fully-functioning Hindu temple, where devotees, young and old, Western and Indian, householder and renunciant, can pour forth their hearts’ yearning to the Great Mystery at the centre of existence. Sri Ramakrishna’s life and teachings point unequivocally towards spiritual freedom. It is not birth, not upbringing, not culture that decides your path. It is yearning. With yearning for the Divine, it does not matter what path you walk; and without yearning, you will not be able to walk any path. Sri Ramakrishna reveals the purest and safest approach to an oft en misunderstood goddess. There are many ways of worshipping Kali. While many may be authentic, not all are safe. Sri Ramakrishna mastered the sixty-four branches of tantra—many difficult and controversial. But when the time came to train his own disciples, he made the path to God simple and beautiful. He said: ‘Pray to the Divine Mother with a longing heart. Her vision dries up all craving for the world and completely destroys all attachment to “woman and gold”. It happens instantly if you think of Her as your own mother. She is by no means a godmother. She is your own mother.’

Today, 150 years after his birth, we are still calculating the tremendous impact this ‘little child’ has had on the world. Sri Ramakrishna held the key to the Mother’s treasure, and Swami Vivekananda, in his brief, blazing life of service, accomplished her work, without a doubt. But Mother’s great miracle is that he then left the key for anyone of us to find, if we but surrender to her. ‘This attitude of regarding God as Mother,’ Sri Ramakrishna said, ‘is the last word in sadhana. “O God, Thou art my Mother and I am Thy child”—this is the last word in spirituality.’

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.